from the National Humanities Center |

|

| |

|

|

| NHC Home |

|

African American Christianity, Pt. I: | |||||||||||||||

|

To the Civil War Laurie Maffly-Kipp University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill ©National Humanities Center |

| ||||||||||||||

(part 2 of 3)

Northern Blacks and the Independent Black Church Movement

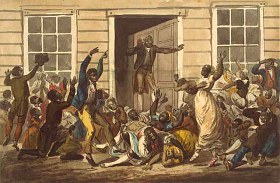

John Lewis Krimmel, Black People's Prayer Meeting, watercolor, ca. 1811, depicting a Methodist service in Philadelphia Meanwhile, in the northern states, freed blacks enjoyed a greater, if not yet equal, measure of freedom. Like their southern counterparts, they, too, were drawn to evangelical Protestant churches, and were encouraged by the message of racial equality that they found there. Yet while spiritual equality was preached frequently, it was not always practiced. By the 1790s, as more and more migrants fled southern states and settled in northern cities, some white evangelical leaders sought to control black members by seating them separately and by strengthening white control over the churches.

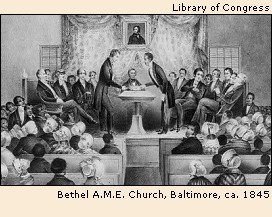

At the same time black leaders such as Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, many of whom were educated, literate, and ready to organize, began to desire their own independent black churches. In cities with large numbers of freed blacks such as Philadelphia, Boston, and New York, leaders broke away from white Methodists and Baptists. By 1816, the first independent black denomination, the African Methodist Episcopal Church, came into existence, and was quickly followed by the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in 1821.

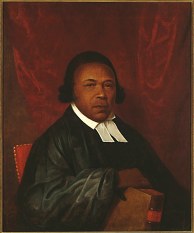

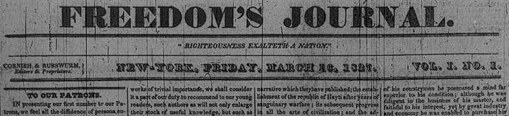

R. Peale, Absalom Jones, oil on paper, 1810 In these independent churches, African Americans combined evangelical zeal with work on behalf of struggling free blacks and antislavery advocacy. Because limited educational and vocational opportunities were open to blacks in northern states, churches also served as schools, training centers, and centers of community organization. Many of the early black newspapers published were facilitated or spearheaded by black clergy, and thus the churches helped to bring African Americans across distances together into a more self-conscious community. They also linked African Americans to wider networks of evangelical life in Great Britain, the Caribbean, and the small communities of migrants who were moving to the colonies of Sierra Leone and Liberia after the 1820s, thereby sowing the seeds for an international "Pan-African" movement. Indeed, some of the first "black nationalists," leaders who advocated for the full rights of African Americans and who favored a worldwide political movement of African-descended peoples, were Protestant clergy.

|

||||||

It should also be remembered, though, that a sizeable number of free black Protestants chose not to join independent black churches, but remained in biracial Presbyterian, Congregational, or Episcopalian congregations. Some also sought religious experience in the many new religious movements, from the Shakers to the Mormons, that emerged in the evangelical awakenings of the 1820s and 1830s. Though their numbers were quite small, it is clear that the social unrest and creativity catalyzed by awakening left small openings for interracial community and often more egalitarian styles of life than those offered by traditional Protestant churches. Just as was true of whites in the antebellum era, free blacks took advantage of the many opportunities for "religious seeking" that came their way.

Guiding Student Discussion

"By the time of the Civil War, black worship in the north and the south

were very different."

It is important to emphasize to students that not all African Americans were slaves during the nineteenth century, and that the realities of life in the north and south for blacks, which were quite different, led inevitably to different kinds of religious patterns and organizations. In the north, educated blacks often assimilated very successfully into white culture (exemplified by the poetry of Phillis Wheatley, for example); indeed, that was precisely the goal for many. Thus, their churches most often replicated white evangelical patterns very closely, although they almost always injected an antislavery message into their social work. In the south, where slaves often remained much more isolated from whites, and where the "white church" often seemed like a sham, the invisible institution aided in the retention of many more African practices and beliefs that were incorporated into Christian worship. By the time of the Civil War, then, black worship in the north and the south were very different. [See Primary Sources.]

"Lament of the Slave," by a "Freedomite," Palladium of Liberty (freedmen's newspaper),

10 July 1844

full imageAt this point, students may be tempted both to dismiss northern blacks as mere imitators of white customs and embrace the "authentic" nature of southern black worship, or, if they themselves have deeply held evangelical commitments, they may judge slave worship as hopelessly non-Christian because of its incorporation of African-based music and bodily movement. The challenge is to present the context for both of these styles of worship such that students see why black believers in both the south and the north might have called themselves Christian, and might have practiced Christianity in the ways that they did. How did the social and political circumstances in which they lived shape their religious expression? Why would southern blacks have so closely associated the ideas of spiritual and political freedom, and northern blacks have been more careful to present their views as traditionally Protestant?

Aside from the obvious differences between northern and southern blacks, students may be fascinated, or utterly baffled, by the motivations of both blacks and whites in the South. Why would white owners have wanted to convert slaves to Christianity? What advantages and disadvantages would conversion have held for them? What tensions might revivalism have raised between slaves, white owners, and evangelical ministers? Why would slaves have wanted to adopt the religion of their masters? What did it mean, in practical terms, to be both spiritually free yet still owned as property? Finally, the big question: Was evangelical religion ultimately a positive thing for blacks, both southern and northern, or did it only help to make them obedient in the face of white oppression?

TeacherServe Home Page

National Humanities Center Home Page

7 Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256

Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709

Phone: (919) 549-0661 Fax: (919) 990-8535

Revised: June 2005

nationalhumanitiescenter.org