|

| NHC Home |

|

The Challenge of the Arid West Donald Worster, University of Kansas ©National Humanities Center |

|

(part 3 of 4)

Guiding Student Discussion (continued)

Is this a limitation created by nature or culture? Consult Jared Diamond (Guns, Germs, and Steel, 1997) for a provocative discussion of what was biologically possible and what was not in the history of domestication. Even now we have not learned how to turn the creosote bush into practical food or build an agricultural economy on it. Thus, biology and culture converged to say that it would be impossible to farm out here unless you did what people in arid lands have always done: adopt a low-intensive, pastoral way of life or bring water to your crops artificially. Americans eventually adopted those novel forms of agriculture—they had to. But, again, they did so in ways determined by both culture and nature. The need for calories and energy was the same for all people. However, rights to water, the amounts of water sought and applied, and the full purposes of agricultural production all differed from one ethnic group to another. Here you might compare the methods that different societies employed in irrigation: those of the native Americans such as the Hohokam, the Spanish in colonial New Mexico or California, the Mormons working under the supervision of their church, and the more secular-minded, profit-seeking Americans (see online resources).

for 400 years, Arizona, 1899"However, rights to water, the amounts of water sought and applied

. . . all differed from one ethnic

group to another."Orchard Mesa

irrigation ditch

Colorado, 1911 (?)Denver Public Library The typical response of students confronting something as large as the West and its modern technology of water management is to feel that all this history was inevitable—and perhaps wonderful. We did what we had to. We triumphed. Now we can forget about the problem of aridity. But if the purpose of studying history is to make us better able to handle complexity and change, then teachers need to work hard to overcome both that feeling of historical inevitability and the cheerful apathy it often engenders.

Kansas, n.d.

Valley, California, 1972

In the first place, the climate of the West has never been a fixed state of nature that, once understood, could be predicted and controlled. What was wet sometimes abruptly became arid, and what was arid sometimes became even more arid. Nature's own history has been as volatile and changing as the history we have made. The water that was stored in reservoirs like Utah's Lake Powell seeped into porous sandstone, or evaporated, until westerners often ended up with less water than they started with. Silt collected behind their dams, making them only temporary solutions. And salinization of the soil followed like a curse wherever intensive irrigation was practiced. A good question for discussion then is how long will a dynamic, irrepressible nature allow us to maintain the hydraulic civilization we have built?

Large silt plume in reservoir off Lake Powell, 1989 Bill Wolverton

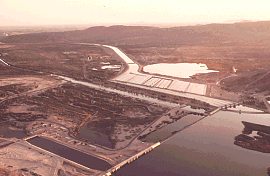

Desilting basins for

Imperial Dam, Arizona, 1972

View NASA imageNational Archives "how long will a dynamic, irrepressible nature allow us to maintain the hydraulic civilization we have built?" A second question for discussion that complicates this story is how government policy shaped the outcome that we see today. Policies that subsidized railroads, offered generous land grants, and encouraged immigration deliberately pushed people into the teeth of aridity. It is worth asking what the West would have become without those policies. Or without the massive investment of capital and expertise that the government made, especially from the 1930s through the 1960s, to capture water for western development. What would Los Angeles look like without that government intervention to find more water?

Over the past few decades the nation has been reappraising its efforts to develop the arid West. Students should try to connect the past to current debates between environmentalists and developers, between rival users who want more water than they are getting, and between regions of the country over who should pay the cost of maintaining a civilization in the desert. Should we support more golf courses or urban growth, should we preserve the few remaining wild rivers, or should we cut down on the amount of water going to agricultural interests (typically 80 to 90 percent of the supply in western states)? Should water become more of a market commodity than it is now and be sold to the highest bidder? Does the desert have any value beyond economics? Has our history left ordinary citizens in control, or has it created a powerful elite who make the decisions? As hard as it may be to imagine how people once experienced aridity first-hand, it is even harder to grapple with the complex decisions that must be made about aridity today. Or to respond to nature's limits and uncertainties.

Moab, Utah bordering

on Canyonlands National Park"Over the past few decades

the nation has been

reappraising its efforts

to develop the arid West."

| "Wilderness and American Identity" Essays |

| The Puritan Origins of the American Wilderness Movement | The Challenge of the Arid West | Rachel Carson and the Awakening of Environmental Consciousness Essay-Related Links |

TeacherServe Home Page

National Humanities Center

7 Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256

Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709

Phone: (919) 549-0661 Fax: (919) 990-8535

Revised: July 2001

nationalhumanitiescenter.org