The Challenge of the Arid West

Donald Worster, University of Kansas

©National Humanities Center

|

|

(part 1 of 4)

|

Death Valley National

Monument, California

| Charles Webber

California Academy

of Sciences

|

"the relative emptiness of much of the West is due to the persisting power of

nature to set terms to human life"

|

|

|

|

Flying west across the continent, the traveler notices a dramatic change in the American landscape—from wet to dry, from green forests and cornfields to sagebrush plains and harsh deserts with only

scattered stands of trees at the higher elevations. For more than a century now we have called that dry

half of the continent the West. It starts on the Great Plains and stretches over a thousand dusty miles to

sun-baked Los Angeles and an anomalous fringe of temperate rain forest in the Pacific Northwest.

Today, millions of people live here, but they tend to concentrate in a few places—oases where water is

delivered—rather than spreading out on the ground. In fact, much of this region is still unsettled (with

fewer than two people per square mile) and likely will never become settled. That fact is not due to any

of the historical forces we commonly talk about—Puritanism, the Enlightenment, capitalism, slavery, or

television—although they all have had their influence on this region. No, the relative emptiness of much

of the West is due to the persisting power of nature to set terms to human life.

|

|

|

Santa Fe, New Mexico

1873

| National Archives

|

"They debated the West's promise: would it set a rigid limit on the country's growth . . . or would it be redeemable by agriculture and other forms of labor?"

|

|

|

Each set of people who have come into this country has had to deal with those environmental realities.

Only the Spanish-speaking immigrants from the Iberian Peninsula, which is similarly arid, came with

much experience; other immigrants from ancient or modern Asia, Africa, or northern Europe have had a

lot more to learn. Growing numbers of Americans began to encounter the arid West in the 1820s,

journeying along the Santa Fe Trail, and in the 1840s, when the Mormons arrived in Utah while

hundreds of thousands of other citizens plodded farther overland to find California gold. They debated

the West's promise: would it set a rigid limit on the country's growth, a "Great American Desert" that

had little to offer, or would it be redeemable by agriculture and other forms of labor?

|

|

|

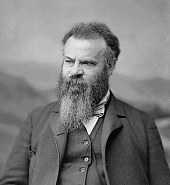

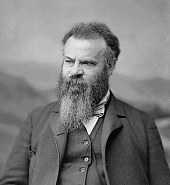

John Wesley Powell

| National

Archives

|

"Americans must learn to work together, he argued, if they wanted to see the West support secure, prosperous homes"

|

|

|

In 1878 John Wesley Powell, who led the first exploration of the upper Colorado River and the Grand

Canyon, published a government report on "the arid region," which he defined as the territory west of

the hundredth meridian. That line approximates the point where rainfall drops to less than twenty inches

per year on average, which was not enough to sustain the leading domesticated crops. Powell

recommended sweeping changes in the public land laws to allow small, irrigated farms and livestock ranches, but also to encourage

|

|

Powell expedition

Wyoming Territory

1871

| National Archives

|

|

|

|

a less individualistic way of living on the land. Americans must learn to

work together, he argued, if they wanted to see the West support secure, prosperous homes, and always

they must worry about the threat of monopoly over the vital natural resource of water.

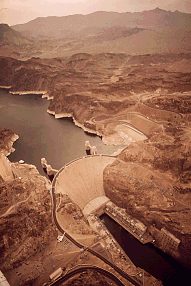

The twentieth century has launched massive projects to control and manage the scarce water supply,

most dramatically with the dedication of Hoover Dam in 1935. Thousands of large and small dams,

canals, reservoirs, and aqueducts eventually captured the water from far-apart rivers and transported it

to agriculturists and to city consumers. Still, the West remains predominately brown, barren, and starkly

defiant. Americans may have constructed a "hydraulic civilization" here, a society dependent on large-scale hydraulic engineering for survival, but they have not really turned scarcity into unlimited

abundance. The battle to control water, which has been at the heart of the West's history, goes on, and

none of the engineering marvels is secure or permanent. The fact that huge numbers of people now live

here, that aridity did not stop the westward movement dead in its tracks, does not mean that, in the end,

nature had no power or influence over American history, or is no longer a threat to the future.

| Roosevelt Dam, Arizona, 1916

View a 1928 film on the dam

| Library of Congress

|

"The battle to control water, which has been at the heart of the West's history, goes on, and none of the engineering marvels is secure or permanent."

|

|

TeacherServe Home Page

National Humanities Center

7 Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256

Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709

Phone: (919) 549-0661 Fax: (919) 990-8535

Revised: July 2001

nationalhumanitiescenter.org |