|

|

|

|

|

Reading Guide |

| 5. |

Citizens

| - | Equal Suffrage. Address from the Colored Citizens of Norfolk, Va., to the People of the United States, 1865, excerpts |

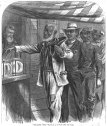

| - | Alfred R. Waud, The First Vote, illustration in Harper's Weekly, 16 Nov. 1867 |

|

|

|

In the months after war's end in April 1865, African Americans met in annual "colored citizens'" conventions across the nation and issued heart-felt "addresses to the people of the United States," affirming their status as citizens and imploring the support of fair-minded white people. From Charleston, Mobile, Nashville, Alexandria, Norfolk, Chicago, Detroit, Sacramento and many other cities came these calls to justice, which were published and circulated. As the Norfolk citizens stated in the address included here, "God grant they may never have to say that they . . . appealed in vain" to the American people.

Through the late 1860s it seemed that this promise might be realized. The three "Civil War Amendments" were ratified in these years—they banned slavery (the 13th in 1865), made the freed slaves citizens of the nation and of their states (the 14th in 1868), and granted them the right to vote (the 15th in 1870, although southern states quickly passed laws to block freedmen's suffrage). Speaking directly to the defeated Confederacy, Congress stated in the 14th Amendment that no state could "deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." Although these guarantees remained only words until the next century, they molded the promise of citizenship held by freedmen and northerners and rendered in The First Vote, an 1867 illustration published in Harper's Weekly as part of its extensive coverage of the postbellum South. 7 pages.

Discussion questions

- How do the Norfolk citizens appeal to patriotism, Christian values, national stability, and simple pragmatism in their call for equal suffrage?

- Compare their nine resolutions with the 1906 Declaration of Principles issued by the Niagara Movement (see POLITICS).

- What does The First Vote reveal about the status of the black voter in 1867?

- What do you make of Waud's use of light, his use of the national flag, and his choice of representative characters?

- In 1867 how might a northern viewer have interpreted this scene? a freedman? a southerner?

- How important is suffrage for the realization of freedom?

|

» Link |

|

|

Topic Framing Questions

| • |

What challenges did the newly freed African Americans face immediately after the Civil War? |

| • |

What did freedom mean to the newly freed? |

| • |

What resources did recently emancipated African Americans possess as they assumed life as free men and women?

|

| • |

How did African Americans define and exercise power in their first years of freedom?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|