The American Civil War: An Environmental View

Jack Temple Kirby, Miami University

©National Humanities Center |

|

(part 6 of 6)

GUIDING STUDENT DISCUSSION

Charles Frazier's acclaimed recent novel Cold Mountain (soon to be a movie) is wonderfully evocative of landscape's physical and psychological powers over men and women who lived during the third quarter of the nineteenth century. Frazier's protagonists manage to speak in language true to their time that engrosses us, too. This fiction is excellent Civil War history, environmentally and otherwise. Yet Cold Mountain is no substitute for the comprehensive environmental treatment that still does not exist. As suggested above, teachers must apply their own green orientation to re-reading the literature old and new. The following points and procedures may be helpful in the classroom as well.

1. Attitude toward nature. Virtually all Americans alive when the Civil War began viewed nature with due respect, even fear, but as an enemy to civilization, and they usually saw themselves as agents of God's injunction to civilize. Henry David Thoreau and the painter George Catlin, who first championed wilderness during the 1830s and '40s, were exceptions demonstrating the rule.

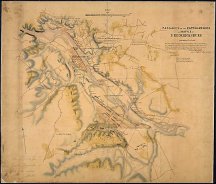

2. War and engineering. Throughout history, civilizers have often been engineers. The education of field commanders in the war, quite sensibly, stressed engineering. War takes place on specific landscapes in certain climates. Officers must be schooled to map and measure, and to manipulate landscape where possible and necessary—construct roads, bridges,

fortifications, and even redirect streams. (U. S. Grant tried to re-route the Mississippi River

during the Vicksburg campaign.) The

shovel, saw, hammer, and horse- or mule-team were no less important implements of war than cannon, rifled musket, and sword. The modern profession of engineering, with it various specialities, began to emerge after the war; but it is appropriate to identify Grant, Robert E. Lee, William Tecumseh Sherman, and other generals as civil engineers as much as battle leaders. The U.S. Army's centrality to landscape manipulation continues to this day with its Corps of Engineers, which is responsible for maintenance of river and harbor navigation, and which has built as many dams as the Interior Department's Bureau of Reclamation.

3. Battlefield maps. Engineer-warriors must have maps or they are lost. Civil War officers' correspondence and reports are often consumed with maps and landscape details, and engineers of both sides produced excellent new maps of strategic parts of the South that survive. When I was researching the swampy countryside between the James River and Albemarle Sound, I discovered that the Virginia Historical Society had reproduced a large collection of Confederate maps of Virginia and North Carolina, printing them in the original format of approximately two-by-three feet. The maps are, quite simply, beautiful as well as useful, presenting not only essential roads, railways, and watercourses, but wetlands, forests, and farm clearings often labeled with owners' names. Such lovely maps present a problem nonetheless: how to orient oneself to visit map sites and compare landscape features? My solution, usually, was acquisition of yet more maps—U.S. Geological Survey quadrangle maps (available at low cost from state agencies), many made during the 1960s and revised in color during the 1980s. (Since I completed my studies, a company in Maine called De Lorme has advertised for sale digitized quadrangles on CD-ROM.) Map comparisons have obvious pedagogical promise beyond military history, of course.

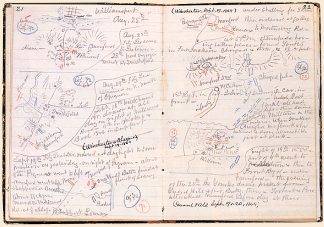

Library of Congress  |

Sketch notes of Confederate topographical engineer

Jedediah Hotchkiss

written en route

from Williamsport to Winchester, Virginia,

August/September 1864

image enlargement |

|

4. Battlefield visits. If feasible, a class trip to a battlefield park would be the capstone of students' classroom re-visioning of the war. My own experience at Gettysburg changed my notions of doing research. Ever the indoor worker dependent upon printed material—archives of letters, documents, and maps—I almost never visited out-of-the-way historical sites. But in June of 1985 I happened to be in Baltimore with my family and decided to return to Ohio by way of Gettysburg. My children would benefit, I thought, and not only had I read accounts of the three-day battle in school but I'd heard about it all my life.

|

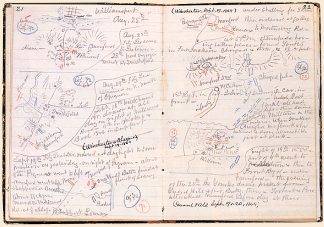

Panorama of second day's battle, photographed

in 1909

| Library of Congress |

"My own experience at Gettysburg changed my notions of doing research."

|

|

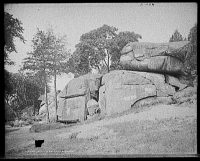

Several of my ancestors were Confederate soldiers who participated in the campaign. One of them, Captain James Kirby, commanded a battery of artillery in Longstreet's Corps, which General Lee ordered to attack the southern end of the Union line on the second day. The Union line was anchored by odd geological formations called Round Top and Little Round Top. Longstreet preferred to flank them; but Lee, overconfident, ordered him to press through the Peach Orchard, the Wheat Field, through Devil's Den, then somehow to topple the Round Tops. Longstreet (and my great-grandfather)

failed and never heard the end of it, Longstreet becoming the Confederate scapegoat after the war. More than half a century later, too, ancient veterans regaled my father (then a small boy in a Virginia town) with tales of his grandfather's prowess with cannon. My father repeated the stories to me, but always with the profound reservation that at Gettysburg, Captain Kirby failed and the Confederacy was lost.

Of that I am profoundly glad. Still, I was more eager to see the Round Tops than any other part of the battlefield. When they at last appeared before me, I was amazed: enormous boulders I could never have imagined in southeastern Pennsylvania—more likely in Utah, I figured, except for the distinctly eastern thickets surrounding the giant rocks.

No

disrespect to the brave Maine men who defended these high boulders, but I finally realized something very simple: no wonder

Longstreet and my great-grandfather failed. What they needed was an air strike, and the smell of napalm in the morning! Longstreet had been right. Lee ignored his map and geology, with consequences indeed.

SCHOLARS DEBATE

As already observed, Civil War scholars and

environmental historians have not so much debated as ignored each other. Among

many fine, big, and well-written war books of recent years, however, Charles

Royster's The Destructive War: William Tecumseh Sherman, Stonewall Jackson,

and The Americans (Knopf, 1991) engages the notion and practice of

"total war" in the nineteenth century and is memorable for Royster's

account of the burning of Columbia, South Carolina. Environmental works on the

South are few and fewer still directly address the war. See Albert Cowdrey, This

Land, This South: An Environmental History (University of Kentucky Press,

1983), and, on coastal Georgia, Mart A. Stewart, "What Nature Suffers

to Groe": Life, Labor, and Landscape of the Georgia Coast, 1680-1920

(University of Georgia Press, 1996). My longitudinal study of lowland Virginia

and North Carolina, Poquosin: A Study of Rural Landscape and Society

(University of North Carolina Press, 1995) assesses the war's manifold

environmental consequences on a patch of the South.

Jack Temple Kirby holds a doctorate from the University of Virginia and is W. E. Smith Professor of History at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. Among his published works are Rural Worlds Lost: The American South, 1920-1960 (1987), Poquosin: A Study of Rural Landscape and Society (1995), Nature's Management (2000), a collection of Edmund Ruffin's landscape writings from 1822 to 1859, and "Designs Necessary and Sublime: Historical/Aesthetic Meditations on Agriculture," Harvard Design Magazine (Winter/Spring, 2000). He is a past president of the Agricultural History Society. In the early 1990s he directed two NEH summer seminars on American environmental history for high school teachers.

Address comments or questions to Professor Kirby through TeacherServe "Comments and Questions."

TeacherServe Home Page

National Humanities Center

7 Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256

Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709

Phone: (919) 549-0661 Fax: (919) 990-8535

Revised: July 2001

nationalhumanitiescenter.org |

Links to Online Resources

Illustration Credits

Works Cited