How to Read a Slave Narrative

Historical Overview of an American Tradition

Under the general rubric of slave narrative falls any account of the life, or a major portion of the life, of a fugitive or former slave, either written or orally related by the slave himself or herself. Slave narratives comprise one of the most influential traditions in American literature, shaping the form and themes of some of the most celebrated and controversial writing, in both autobiography and fiction, in the history of the United States. Although the vast majority of American slave narratives were authored by people of African descent, African-born Muslims who wrote in Arabic, the Cuban poet Juan Francisco Manzano, and a handful white American sailors taken captive by North African pirates also penned narratives of their enslavement during the nineteenth century. From 1760 to the end of the Civil War in the United States, approximately one hundred autobiographies of fugitive or former slaves appeared. After slavery was abolished in North America in 1865, at least fifty former slaves wrote or dictated book-length accounts of their lives. During the Depression of the 1930s, the Federal Writers Project gathered oral personal histories from 2,500 former slaves, whose testimony eventually filled eighteen volumes. The narratives of former slaves in the United States continue to be discovered and published, most recently David Blight’s A Slave No More: Two Men Who Escaped to Freedom, Including Their Own Narratives of Emancipation (2007). (See also "Frederick Douglass and Harriet Jacobs: American Slave Narrators" in Freedom's Story.)

The earliest slave narrative to receive international attention was the two-volume Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African (1789), which traces Equiano’s career from West African boyhood, through the dreadful transatlantic Middle Passage, to eventual freedom and economic success as a British citizen. Although some scholarship has questioned the authenticity of Equiano’s claim to African birth, his autobiography is unquestionably the first to challenge on moral and religious grounds the popular acceptance of slavery as a socio-economic institution in eighteenth-century England and the Americas. The first fugitive slave narrative in the United States, the Life of William Grimes, the Runaway Slave, Written by Himself (1825), revealed for the first time to readers in the North the horrors of chattel slavery in the American South and the pervasiveness of racial injustice in New England.

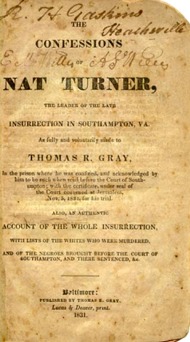

Title page, The Confessions of Nat Turner. |

|

In the aftermath of the Turner revolt and the South’ s iron-fisted response to it, a new generation of reformers in the North proclaimed their uncompromising opposition to slavery. Led by the crusading white journalist William Lloyd Garrison, these abolitionists demanded the immediate end of slavery throughout the United States. Free blacks in the North lent their support to Garrison’s American Anti-Slavery Society, editing newspapers, holding conventions, circulating petitions, and investing their money in protest actions. Searching for a means of galvanizing public concern for the slave as “a man and a brother,” this generation of black and white radical abolitionists began actively soliciting and publicizing the narratives of fugitive slaves. From 1830 to the end of the slavery era, the fugitive slave narrative dominated the literary landscape of antebellum black America, far outnumbering the autobiographies of free people of color, not to mention the handful of novels published by African Americans. Most of the major authors of African American literature before 1865, such as Frederick Douglass, William Wells Brown, and Harriet Jacobs, launched their writing careers via narratives of their experience as slaves.

Advertised in the abolitionist press and sold at antislavery meetings throughout the English-speaking world, a significant number of antebellum slave narratives went through multiple editions and sold in the tens of thousands. The widespread, sometimes international, popularity of the narratives of celebrated fugitives such as Douglass, William Wells Brown, Henry Box Brown, Henry Bibb, and William and Ellen Craft was not solely attributable to the publicity the narratives received from the antislavery movement. Readers could see that, as one reviewer put it, "the slave who endeavours to recover his freedom is associating with himself no small part of the romance of the time." To the noted transcendentalist clergyman Theodore Parker, slave narratives qualified ironically as the only indigenous literary form that America, the reputed “land of the free,” had contributed to world literature. To Parker, "all the original romance of Americans is in [the slave narratives], not in the white man’s novel."

In 1845 the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself became an antebellum international best seller. A fugitive from Maryland slavery, Douglass spent four years honing his skills as an abolitionist lecturer before setting about the task of writing his autobiography. The genius of Douglass’s Narrative, often considered the epitome of the slave narrative before 1865, was its linkage of the author’s adult quest for freedom to his boyhood pursuit of literacy, thereby creating a lasting ideal of the African American hero committed to intellectual achievement and independence as well as physical freedom. During the first five years of its publication, the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave is estimated to have sold at least 30,000 copies, a greater number of sales than Moby-Dick (1851), Walden (1854), and Song of Myself (1855) could have amassed in common during the first five years of their publication.

In the late 1840s well-known fugitive slaves such as William Wells Brown, Henry Bibb, James W. C. Pennington, and William and Ellen Craft reinforced the rhetorical self-consciousness of the slave narrative by incorporating into their stories trickster motifs from African American folk culture, extensive literary and biblical allusion, and a picaresque perspective on the meaning of the slave’s flight from bondage to freedom. As social and political conflict in the United States at mid-century centered more and more on the presence and fate of African Americans, the slave narrative took on an unprecedented urgency and candor, unmasking as never before the moral and social complexities of the American caste and class system in the North as well as the South. My Bondage and My Freedom (1855), Douglass’s second autobiography, conducted a fresh inquiry into the meaning of slavery and freedom, adopting the standpoint of one who had spent enough time in the so-called “free states” to understand how pervasive racism and paternalism were, even among the most liberal whites, the Garrisonians themselves. Harriet Jacobs, the earliest known African American female slave to author her own narrative, also challenged conventional ideas about slavery and freedom in her strikingly original Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself (1861).

Jacobs’s autobiography shows how sexual exploitation made slavery especially oppressive for black women. But in demonstrating how she fought back and ultimately gained both her own freedom and that of her two children, Jacobs proved the inadequacy of the image of victim that had been pervasively applied to female slaves in the male-authored slave narrative. The writing of Jacobs; the feminist oratory of the "Libyan sybil," Sojourner Truth; and the renowned example of Harriet Tubman, the fearless conductor of runaways on the Underground Railroad, enriched African American literature with new models of female self-expression and heroism.

In the 1850s, slave narratives contributed to the mounting national debate over slavery. The most widely read and hotly disputed American novel of the nineteenth century, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), was profoundly influenced by its author’ s reading of slave narratives, to which she owed many graphic incidents and the models for some of her most memorable characters. Uncle Tom, she explained, had been inspired by her reading of The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada (1849). Stowe’s novel, in turn, spurred the publication of narratives that promised to out-do her in exposing the full truth about the horrors of slavery. The most famous—and widely read—was Solomon Northup’s ghostwritten autobiography, whose title summed up his shocking story: Twelve Years a Slave: Narrative of Solomon Northup, a Citizen of New-York, Kidnapped in Washington City in 1841, and Rescued in 1853, from a Cotton Plantation Near the Red River, in Louisiana (1853).

After the abolition of slavery in 1865 former slaves continued to publish their autobiographies, often to show how the rigors of slavery had prepared them for full participation in the post-Civil War social and economic order. A notable example of the post-Civil War slave narrative flowed from the pen of Elizabeth Hobbs Keckley, whose Behind the Scenes: or, Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House (1868) recounted the author’s successful rise from enslavement to independent businesswoman and confidante to the First Lady of the United States, Mary Todd Lincoln. In November 1874, Mark Twain broke into the prestigious Atlantic Monthly with “A True Story, Repeated Word for Word as I Heard It,” the narrative of Mary Ann Cord, the Clemens family cook, who had been enslaved for more than sixty years before emancipation. Ten years later, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, ostensibly the autobiography of a poor-white teenager who tries to help an older slave escape, became a major white contribution to the American fugitive slave narrative. The biggest selling of the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century slave narratives was Booker T. Washington’s Up from Slavery (1901), a classic American success story that extolled African American progress and interracial cooperation in the Black Belt of the deep South since the end of slavery in 1865. Notable twentieth-century African American autobiographies, such as Richard Wright’s Black Boy (1945) and The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965), as well as prize-winning novels such as William Styron’s The Confessions of Nat Turner (1967), Ernest J. Gaines’s The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (1971), Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1989), and Edward P. Jones’s The Known World (2004), bear the unmistakable imprint of the slave narrative, particularly in probing the origins of psychological as well as social oppression and in their searching critique of the meaning of freedom for twentieth-century black and white Americans alike.

Guiding Student Discussion

What does the title page of a slave narrative tell us?

| [+] | [+] | |

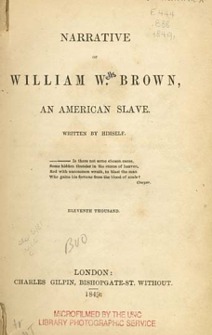

Title page, Narrative of William W. Brown, an American Slave. |

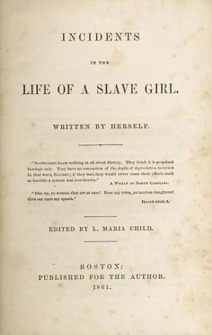

Title page, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. |

The title page of a slave narrative bears significant clues as to the authorship of the narrative itself. Subtitles often convey the role that the subject named in the narrative’s title actually played in the production of the narrative. The narratives of Equiano, Grimes, Douglass, Wells Brown, and Bibb, for instance, all bear the subtitle Written by Himself. Though the title page of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl does not name the “Slave Girl” whose life story follows, the subtitle of the book states that it was Written by Herself. Narratives that identify the subject and author of the text as one and the same represent, in the eyes of many scholars, the most authoritative texts in the tradition. Ask students why it would be important for white readers of the mid-nineteenth century to see the Written by Himself or Herself subtitle in these narratives? Why is authorship of one’s own story so important? Students should understand that identifying a slave narrator as literate and capable of independent literary expression was a powerful way to combat a key proslavery myth, which held that slaves were unself-conscious and incapable of mastering the arts of literacy. Students should remember that in mid-nineteenth-century America, where many whites had had little or no schooling, literacy was a marker of social prestige and economic power.

What is the significance of the prefaces and introductions found in many slave narratives?

Typically, the antebellum slave narrative carries a black message inside a white envelope. Prefatory (and sometimes appended) matter by whites attest to the reliability and good character of the black narrator while calling attention to what the narrative would reveal about the moral abominations of slavery. Notable examples of white prefaces to black texts (only a small minority of nineteenth-century slave narratives carry a preface by a person of African descent) are William Lloyd Garrison’s in Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass and Lydia Maria Child’s in Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. In both cases, the prefaces seek to authenticate the veracity of the narratives that follow them. A good question to ask students is, why did these narratives need such prefaces? Would the race or color of the preface writer—both Garrison and Child were white—matter to the slave narratives’ primarily white readership?

What is the plot of most pre-Civil War slave narratives?

Beyond the prefatory matter, the former slave’s autobiographical narrative generally centers on his or her rite of passage from slavery in the South to freedom in the North. Usually, the antebellum slave narrator portrays slavery as a condition of extreme physical, intellectual, emotional, and spiritual deprivation, a kind of hell on earth. Since most antebellum narratives were intended to serve a propagandistic purpose—to illustrate in graphic but authoritative terms the hardships of actual day-to-day life in slavery—the focus of most of these narratives tends to be more on the institution of slavery rather than on the consciousness of the individual slave. Students will learn a great deal from some narratives—such as those of Grimes, Bibb, and Northup—about the day-to-day grind of back-breaking agricultural labor that we often associate with slavery. Such narratives are not always as self-reflective as readers today might like. Students should understand that fugitive slaves could not assume that whites were interested in what they thought or how they felt about matters other than slavery.

In studying such narratives as Douglass’s, Wells Brown’s, Jacobs’s, and the Crafts’, students might explore what slavery was like for comparatively fortunate slaves. Douglass, for instance, spent a crucial part of his boyhood in a port city where he had access to information and had the opportunity to learn to read. In his young manhood he had the opportunity to learn a trade and hire his time in Baltimore. Wells Brown, another skilled slave, had the advantage of working primarily as a house servant, not a field hand. So did Harriet Jacobs and William and Ellen Craft. Students could ask themselves why slaves with these comparative advantages were the ones who not only risked everything to escape but then wrote so passionately and eloquently about the injustices of their enslavement.

What is the turning-point in a slave narrative? Is it when the slave resolves to escape or when he or she arrives in the North? How does the slave arrive at the decision to escape? Does the narrator portray a process of growing awareness, dissatisfaction, and resistance that culminates in the escape effort?

Most slave narratives portray a process by which the narrator realizes the injustices and dangers facing him or her, tries to resist them—sometimes physically, sometimes through deceit or verbal opposition—but eventually resolves to risk everything for the sake of freedom.

Precipitating the narrator’s decision to escape is usually some sort of personal crisis, such as the sale or death of a loved one (Box Brown), insults and cruelties too great to bear (Pennington), a dark night of the soul (Henson), or simply a rare opportunity too inviting to forego (Jacobs). Many readers were fascinated by the harrowing accounts of flight featured in some of the most popular slave narratives, such as Narrative of Henry Box Brown, Who Escaped from Slavery, Enclosed in a Box 3 Feet Long and 2 Wide (1849) and Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, or, the Escape of William and Ellen Craft from Slavery (1860). Douglass, on the other hand, refused to disclose the means by which he made his escape, thereby directly contradicting the expectations of the form he himself had adopted. Why would Douglass make such a decision, knowing his readership wanted to read these kinds of escape accounts (in his post-Civil War Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, he explained how he made his way to freedom)?

How do most slave narratives end? How do they portray life in the North?

Impelled by faith in God and a commitment to liberty and human dignity comparable (some narrators insist) to that of America’ s Founders, the slave’s arduous quest for freedom almost always climaxes in his or her arrival in the North. In some well-known antebellum narratives, the attainment of freedom is signaled not simply by reaching the so-called free states but by renaming oneself (Douglass and William Wells Brown make a point of explaining why), finding employment, marrying, and, in some cases, dedicating significant energy to antislavery activism. Few slave narratives condemn the widespread racial discrimination and injustice that African Americans endured in the North. The Life of William Grimes is a remarkable exception. If students compare the final paragraphs of this autobiography and the last chapter of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl to the final scene of Douglass’s Narrative (see below), they will have a chance to compare and contrast three different perspectives on life in the North.

Different Perspectives on Life in the North from Three Slave Narratives

From The Life of William Grimes, the Runaway Slave, Written by Himself (1825) PDF file

. . . Those slaves who have kind masters, are perhaps as happy as the generality of mankind. They are not aware that their condition can be better, and I dont know as it can: indeed it cannot by their own exertions. I would advise no slave to leave his master. If he runs away, he is most sure to be taken. If he is not, he will ever be in the apprehension of it. And I do think there is no inducement for a slave to leave his master, and be set free in the northern states. I have had to work hard; I have been often cheated, insulted, abused, and injured; yet a black man, if he will be industrious and honest, he can get along here as well as any one who is poor, and in a situation to be imposed on. I have been very unfortunate in life in this respect. Notwithstanding all my struggles and sufferings, and injuries, I have been an honest man. There is no one who can come forward and say he knows any thing against Grimes. This I know, that I have been punished for being suspected of things, of which, some of those who were loudest against me, were actually guilty. The practice of warning poor people out of town is very cruel. It may be necessary that towns should have that power, otherwise some might be overrun with paupers. But it is mighty apt to be abused. A poor man just gets a going in business, and is then warned to depart. Perhaps he has a family, and dont know where to go, or what to do. I am a poor man, and ignorant. But I am a man of sense. I have seen them contributing at church for the heathen, to build churches, and send out preachers to them, yet there was no place where I could get a seat in the church. I knew in New-Haven, Indians and negroes, come from a great many thousand miles, sent to be educated, while there were people I knew in the town, cold and hungry, and ignorant. They have kind of societies to make clothes, for those, who they say, go naked in their own countries. The ladies sometimes do this at one end of a town, while their father’s who may happen to be selectmen, may be warning a poor man and his family, out at the other end, for fear they may have to be buried at the state expense. It sounds rather strange upon a man’s ear, who feels that he is friendless and abused in society, to hear so many speeches about charity; for I was always inclined to be observing.

I have forebore to mention names in my history where it might give the least pain, in this I have made it less interesting and injured myself.

I may sometimes be a little mistaken, as I have to write from memory, and there is a great deal I have omitted from want of recollection at the time of writing. I cannot speak as I feel on some subjects. If those who read my history, think I have not led a life of trial, I have failed to give a correct representation. I think I must be Forty years of age but don’t know; I could not tell my wife my age. I have learned to read and write pretty well; if I had opportunity I could learn very fast. My wife has a tolerable good education, which has been a help to me.

I hope some will buy my books from charity, but I am no beggar. I am now entirely destitute of property; where and how I shall live I don’t know; where and how I shall die I dont know, but I hope I may be prepared. If it were not for the stripes on my back which were made while I was a slave. I would in my will, leave my skin a legacy to the government, desiring that it might be taken off and made into parchment, and then bind the constitution of glorious happy and free America. Let the skin of an American slave, bind the charter of American Liberty.

From Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861) PDF file

Mrs. Bruce came to me and entreated me to leave the city the next morning. She said her house was watched, and it was possible that some clew to me might be obtained. I refused to take her advice. She pleaded with an earnest tenderness, that ought to have moved me; but I was in a bitter, disheartened mood. I was weary of flying from pillar to post. I had been chased during half my life, and it seemed as if the chase was never to end. There I sat, in that great city [New York], guiltless of crime, yet not daring to worship God in any of the churches. I heard the bells ringing for afternoon service, and, with contemptuous sarcasm, I said, "Will the preachers take for their text, ’Proclaim liberty to the captive, and the opening of prison doors to them that are bound’? or will they preach from the text, ’Do unto others as ye would they should do unto you’?" Oppressed Poles and Hungarians could find a safe refuge in that city; John Mitchell was free to proclaim in the City Hall his desire for "a plantation well stocked with slaves;" but there I sat, an oppressed American, not daring to show my face. God forgive the black and bitter thoughts I indulged on that Sabbath day! The Scripture says, "Oppression makes even a wise man mad;" and I was not wise.

I had been told that Mr. Dodge [Jacobs’s current owner] said his wife had never signed away her right to my children, and if he could not get me, he would take them. This it was, more than any thing else, that roused such a tempest in my soul. Benjamin was with his uncle William in California, but my innocent young daughter had come to spend a vacation with me. I thought of what I had suffered in slavery at her age, and my heart was like a tiger’s when a hunter tries to seize her young.

Dear Mrs. Bruce! I seem to see the expression of her face, as she turned away discouraged by my obstinate mood. Finding her expostulations unavailing, she sent Ellen to entreat me. When ten o’clock in the evening arrived and Ellen had not returned, this watchful and unwearied friend became anxious. She came to us in a carriage, bringing a well-filled trunk for my journey-trusting that by this time I would listen to reason. I yielded to her, as I ought to have done before.

The next day, baby and I set out in a heavy snow storm, bound for New England again. I received letters from the City of Iniquity, addressed to me under an assumed name. In a few days one came from Mrs. Bruce, informing me that my new master was still searching for me, and that she intended to put an end to this persecution by buying my freedom. I felt grateful for the kindness that prompted this offer, but the idea was not so pleasant to me as might have been expected. The more my mind had become enlightened, the more difficult it was for me to consider myself an article of property; and to pay money to those who had so grievously oppressed me seemed like taking from my sufferings the glory of triumph. I wrote to Mrs. Bruce, thanking her, but saying that being sold from one owner to another seemed too much like slavery; that such a great obligation could not be easily cancelled; and that I preferred to go to my brother in California.

Without my knowledge, Mrs. Bruce employed a gentleman in New York to enter into negotiations with Mr. Dodge. He proposed to pay three hundred dollars down, if Mr. Dodge would sell me, and enter into obligations to relinquish all claim to me or my children forever after. He who called himself my master said he scorned so small an offer for such a valuable servant. The gentleman replied, "You can do as you choose, sir. If you reject this offer you will never get any thing; for the woman has friends who will convey her and her children out of the country."

Mr. Dodge concluded that "half a loaf was better than no bread," and he agreed to the proffered terms. By the next mail I received this brief letter from Mrs. Bruce: "I am rejoiced to tell you that the money for your freedom has been paid to Mr. Dodge. Come home to-morrow. I long to see you and my sweet babe."

My brain reeled as I read these lines. A gentleman near me said, "It’s true; I have seen the bill of sale." "The bill of sale!" Those words struck me like a blow. So I was sold at last! A human being sold in the free city of New York! The bill of sale is on record, and future generations will learn from it that women were articles of traffic in New York, late in the nineteenth century of the Christian religion. It may hereafter prove a useful document to antiquaries, who are seeking to measure the progress of civilization in the United States. I well know the value of that bit of paper; but much as I love freedom, I do not like to look upon it. I am deeply grateful to the generous friend who procured it, but I despise the miscreant who demanded payment for what never rightfully belonged to him or his.

I had objected to having my freedom bought, yet I must confess that when it was done I felt as if a heavy load had been lifted from my weary shoulders. When I rode home in the cars I was no longer afraid to unveil my face and look at people as they passed. I should have been glad to have met Daniel Dodge himself; to have had him seen me and known me, that he might have mourned over the untoward circumstances which compelled him to sell me for three hundred dollars.

When I reached home, the arms of my benefactress were thrown round me, and our tears mingled. As soon as she could speak, she said, "O Linda, I’m so glad it’s all over! You wrote to me as if you thought you were going to be transferred from one owner to another. But I did not buy you for your services. I should have done just the same, if you had been going to sail for California to-morrow. I should, at least, have the satisfaction of knowing that you left me a free woman."

My heart was exceedingly full. I remembered how my poor father had tried to buy me, when I was a small child, and how he had been disappointed. I hoped his spirit was rejoicing over me now. I remembered how my good old grandmother had laid up her earnings to purchase me in later years, and how often her plans had been frustrated. How that faithful, loving old heart would leap for joy, if she could look on me and my children now that we were free! My relatives had been foiled in all their efforts, but God had raised me up a friend among strangers, who had bestowed on me the precious, long-desired boon. Friend! It is a common word, often lightly used. Like other good and beautiful things, it may be tarnished by careless handling; but when I speak of Mrs. Bruce as my friend, the word is sacred.

My grandmother lived to rejoice in my freedom; but not long after, a letter came with a black seal. She had gone "where the wicked cease from troubling, and the weary are at rest."

Time passed on, and a paper came to me from the south, containing an obituary notice of my uncle Phillip. It was the only case I ever knew of such an honor conferred upon a colored person. It was written by one of his friends, and contained these words: "Now that death has laid him low, they call him a good man and a useful citizen; but what are eulogies to the black man, when the world has faded from his vision? It does not require man’s praise to obtain rest in God’s kingdom." So they called a colored man a citizen! Strange words to be uttered in that region!

Reader, my story ends with freedom; not in the usual way, with marriage. I and my children are now free! We are as free from the power of slaveholders as are the white people of the north; and though that, according to my ideas, is not saying a great deal, it is a vast improvement in my condition. The dream of my life is not yet realized. I do not sit with my children in a home of my own. I still long for a hearthstone of my own, however humble. I wish it for my children’s sake far more than for my own. But God so orders circumstances as to keep me with my friend Mrs. Bruce. Love, duty, gratitude, also bind me to her side. It is a privilege to serve her who pities my oppressed people, and who has bestowed the inestimable boon of freedom on me and my children.

It has been painful to me, in many ways, to recall the dreary years I passed in bondage. I would gladly forget them if I could. Yet the retrospection is not altogether without solace; for with those gloomy recollections come tender memories of my good old grandmother, like light, fleecy clouds floating over a dark and troubled sea.

From Narrative of the Life Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself (1845) PDF file

I was quite disappointed at the general appearance of things in New Bedford. The impression which I had received respecting the character and condition of the people of the north, I found to be singularly erroneous, I had very strangely supposed, while in slavery, that few of the comforts, and scarcely any of the luxuries, of life were enjoyed at the north, compared with what were enjoyed by the slaveholders of the south. I probably came to this conclusion from the fact that northern people owned no slaves. I supposed that they were about upon a level with the non-slaveholding population of the south. I knew they were exceedingly poor, and I had been accustomed to regard their poverty as the necessary consequence of their being non-slaveholders. I had somehow imbibed the opinion that, in the absence of slaves, there could be no wealth, and very little refinement. And upon coming to the north, I expected to meet with a rough, hard-handed, and uncultivated population, living in the most Spartan-like simplicity, knowing nothing of the ease, luxury, pomp, and grandeur of southern slaveholders. Such being my conjectures, any one acquainted with the appearance of New Bedford may very readily infer how palpably I must have seen my mistake.

In the afternoon of the day when I reached New Bedford, I visited the wharves, to take a view of the shipping. Here I found myself surrounded with the strongest proofs of wealth. Lying at the wharves, and riding in the stream, I saw many ships of the finest model, in the best order, and of the largest size. Upon the right and left, I was walled in by granite warehouses of the widest dimensions, stowed to their utmost capacity with the necessaries and comforts of life. Added to this, almost every body seemed to be at work, but noiselessly so, compared with what I had been accustomed to in Baltimore. There were no loud songs heard from those engaged in loading and unloading ships. I heard no deep oaths or horrid curses on the laborer. I saw no whipping of men; but all seemed to go smoothly on. Every man appeared to understand his work, and went at it with a sober, yet cheerful earnestness, which betokened the deep interest which he felt in what he was doing, as well as a sense of his own dignity as a man. To me this looked exceedingly strange. From the wharves I strolled around and over the town, gazing with wonder and admiration at the splendid churches, beautiful dwellings, and finely-cultivated gardens; evincing an amount of wealth, comfort, taste, and refinement, such as I had never seen in any part of slaveholding Maryland.

Every thing looked clean, new, and beautiful. I saw few or no dilapidated houses, with poverty-stricken inmates; no half-naked children and barefooted women, such as I had been accustomed to see in Hillsborough, Easton, St. Michael’s, and Baltimore. The people looked more able, stronger, healthier, and happier, than those of Maryland. I was for once made glad by a view of extreme wealth, without being saddened by seeing extreme poverty. But the most astonishing as well as the most interesting thing to me was the condition of the colored people, a great many of whom, like myself, had escaped thither as a refuge from the hunters of men. I found many, who had not been seven years out of their chains, living in finer houses, and evidently enjoying more of the comforts of life, than the average of slaveholders in Maryland. I will venture to assert that my friend Mr. Nathan Johnson (of whom I can say with a grateful heart, "I was hungry, and he gave me meat; I was thirsty, and he gave me drink; I was a stranger, and he took me in") lived in a neater house; dined at a better table; took, paid for, and read, more newspapers; better understood the moral, religious, and political character of the nation,--than nine tenths of the slaveholders in Talbot county, Maryland. Yet Mr. Johnson was a working man. His hands were hardened by toil, and not his alone, but those also of Mrs. Johnson. I found the colored people much more spirited than I had supposed they would be. I found among them a determination to protect each other from the blood-thirsty kidnapper, at all hazards. Soon after my arrival, I was told of a circumstance which illustrated their spirit. A colored man and a fugitive slave were on unfriendly terms. The former was heard to threaten the latter with informing his master of his whereabouts. Straightway a meeting was called among the colored people, under the stereotyped notice, "Business of importance!" The betrayer was invited to attend. The people came at the appointed hour, and organized the meeting by appointing a very religious old gentleman as president, who, I believe, made a prayer, after which he addressed the meeting as follows: "Friends, we have got him here, and I would recommend that you young men just take him outside the door, and kill him!" With this, a number of them bolted at him; but they were intercepted by some more timid than themselves, and the betrayer escaped their vengeance, and has not been seen in New Bedford since. I believe there have been no more such threats, and should there be hereafter, I doubt not that death would be the consequence.

I found employment, the third day after my arrival, in stowing a sloop with a load of oil. It was new, dirty, and hard work for me; but I went at it with a glad heart and a willing hand. I was now my own master. It was a happy moment, the rapture of which can be understood only by those who have been slaves. It was the first work, the reward of which was to be entirely my own. There was no Master Hugh standing ready, the moment I earned the money, to rob me of it. I worked that day with a pleasure I had never before experienced. I was at work for myself and newly-married wife. It was to me the starting-point of a new existence. When I got through with that job, I went in pursuit of a job of calking; but such was the strength of prejudice against color, among the white calkers, that they refused to work with me, and of course I could get no employment.* Finding my trade of no immediate benefit, I threw off my calking habiliments, and prepared myself to do any kind of work I could get to do. Mr. Johnson kindly let me have his wood-horse and saw, and I very soon found myself a plenty of work. There was no work too hard—none too dirty. I was ready to saw wood, shovel coal, carry the hod, sweep the chimney, or roll oil casks,—all of which I did for nearly three years in New Bedford, before I became known to the anti-slavery world.

In about four months after I went to New Bedford, there came a young man to me, and inquired if I did not wish to take the "Liberator." I told him I did; but, just having made my escape from slavery, I remarked that I was unable to pay for it then. I, however, finally became a subscriber to it. The paper came, and I read it from week to week with such feelings as it would be quite idle for me to attempt to describe. The paper became my meat and my drink. My soul was set all on fire. Its sympathy for my brethren in bonds—its scathing denunciations of slaveholders—its faithful exposures of slavery—and its powerful attacks upon the upholders of the institution—sent a thrill of joy through my soul, such as I had never felt before!

I had not long been a reader of the "Liberator," before I got a pretty correct idea of the principles, measures and spirit of the anti-slavery reform. I took right hold of the cause. I could do but little; but what I could, I did with a joyful heart, and never felt happier than when in an anti-slavery meeting. I seldom had much to say at the meetings, because what I wanted to say was said so much better by others. But, while attending an anti-slavery convention at Nantucket, on the 11th of August, 1841, I felt strongly moved to speak, and was at the same time much urged to do so by Mr. William C. Coffin, a gentleman who had heard me speak in the colored people’s meeting at New Bedford. It was a severe cross, and I took it up reluctantly. The truth was, I felt myself a slave, and the idea of speaking to white people weighed me down. I spoke but a few moments, when I felt a degree of freedom, and said what I desired with considerable ease. From that time until now, I have been engaged in pleading the cause of my brethren—with what success, and with what devotion, I leave those acquainted with my labors to decide.

*I am told that colored persons can now get employment at calking in New Bedford—a result of anti-slavery effort.

Further Reading

For carefully edited digital reproductions of all African American slave narratives published in English before 1930, see North American Slave Narratives in Documenting the American South <http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/>. The most comprehensive studies of American slave narratives are: William L. Andrews, To Tell A Free Story: The First Century of Afro-American Autobiography, 1760-1865 (1986); and Frances Smith Foster, Witnessing Slavery: The Development of Ante-bellum Slave Narratives, 2nd ed. (1994). George P. Rawick, ed., The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography, 19 vols. (1972-1976) includes the oral histories of former slaves collected by the Federal Writers Project. Ashraf H.A. Rushdy, Neo-Slave Narratives (1999) examines the impact of the slave narrative on American fiction since 1960. Ira Berlin, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America (1998) is a valuable historical overview of slavery in the United States.

NHC Home | TeacherServe | Divining America | Nature Transformed | Freedom’s Story

About Us | Site Guide | Contact | Search